Behind Janus: Documents Reveal Decade-Long Plot to Kill Public-Sector Unions

The Supreme Court case Janus v. AFSCME is poised to decimate public-sector unions—and it’s been made possible by a network of right-wing billionaires, think tanks and corporations.

February 22 | March Issue

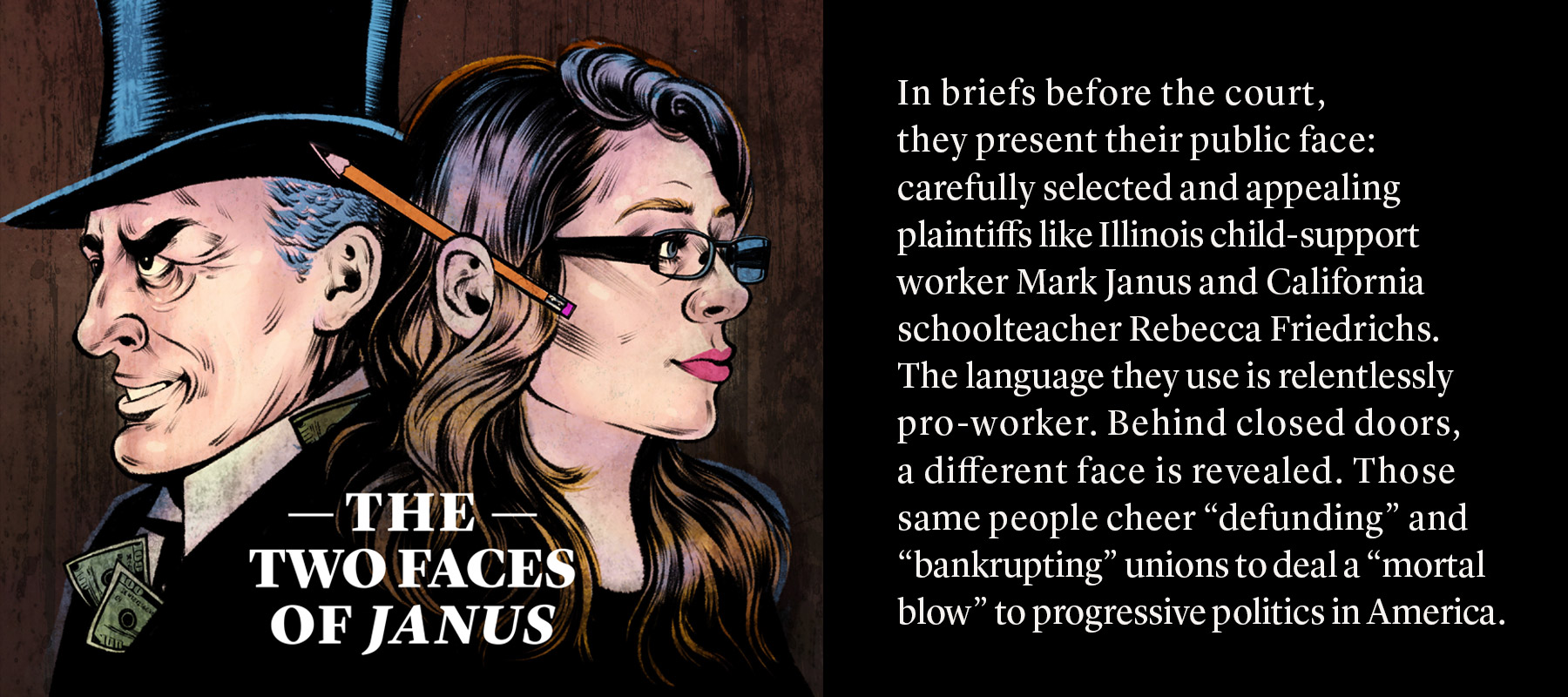

The Roman god Janus was known for having two faces. It is a fitting name for the U.S. Supreme Court case scheduled for oral arguments February 26, Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Council 31, that could deal a devastating blow to public-sector unions and workers nationwide.

In the past decade, a small group of people working for deep-pocketed corporate interests, conservative think tanks and right-wing foundations have bankrolled a series of lawsuits to end what they call “forced unionization.” They say they fight in the name of “free speech,” “worker rights” and “workplace freedom.” In briefs before the court, they present their public face: carefully selected and appealing plaintiffs like Illinois child-support worker Mark Janus and California schoolteacher Rebecca Friedrichs. The language they use is relentlessly pro-worker.

Behind closed doors, a different face is revealed. Those same people cheer “defunding” and “bankrupting” unions to deal a “mortal blow” to progressive politics in America.

A key director of this charade is the State Policy Network (SPN), whose game plan is revealed in a union-busting toolkit uncovered by the Center for Media and Democracy. The first rule of the national network of right-wing think tanks that are pushing to dismantle unions? “Rule #1: Be pro-worker, not anti-union. … Don’t rant against unions. … Using phrases like ‘union fat cats’ and ‘corrupt union bosses’ and other negative language reduces support for reform.”

And yet, SPN groups have systematically spearheaded attacks on unions and workers in statehouses and courtrooms nationwide. The Janus case, and its precursor, Friedrichs v. the California Teachers Association, represent SPN’s most audacious move yet, an effort to kneecap the unions of public-sector workers—including teachers, nurses, sanitation workers, park rangers, prison guards, police and firefighters—in a single blow.

“TRUST TEACHERS!”

On Jan. 11, 2016, about 100 people bundled in coats and mittens mill around the Supreme Court steps. They hold signs with little red apples that read, “Trust Teachers!” and “Respect Teachers? Then respect their First Amendment rights!”

From a distance, it looks like a teachers’ rally. A closer look reveals an odd array of participants. Grover Norquist, the man who wanted to drown government in a bathtub, cheerfully declines an interview as he breezes by. Daniel Turner, who worked for the education reform task force of the far-right American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), waves a “Trust Teachers!” sign from behind the podium. Near him stands Chantal Lovell from SPN’s Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a group credited with jamming a union-busting bill through Michigan’s lame duck legislature in 2012. A representative from SPN’s Arizona-based Goldwater Institute is present, as is a fellow from the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity (who also declines an interview).

The night before, SPN organized a dinner for representatives of its member groups who had flown in for the oral arguments. Among its members were the lawyers representing the plaintiffs in Friedrichs and 12 groups that had filed supporting amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs. The suit was filed on behalf of Rebecca Friedrichs and nine other California teachers who wanted to stop paying their “fair share fees”—money paid by non-union members to cover the costs of collective bargaining.

On the courthouse steps, a woman with a bullhorn tries to rev up the audience. “Who do we trust?” she asks. “Teachers,” murmurs the crowd. “Who?” she yells. “Teachers!” Now they have the hang of it. The podium is emblazoned with the hashtag #IStandWithRebecca.

Friedrichs deadlocked the Court 4-4 after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, leaving the status quo of union fees in place. Expect a repeat of this courthouse scene February 26. SPN is once again rallying the troops and a #StandWithMark hashtag is already circulating.

Janus has its origins in a lawsuit filed by billionaire Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner. Rauner issued an executive order in 2015 instructing Illinois to stop collecting fair share fees. At the same time, he filed a federal lawsuit to speed the issue to the U.S. Supreme Court. Two SPN member groups—the Illinois Policy Institute and the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation—joined the suit with plaintiff Mark Janus, who makes a much more sympathetic poster child than a billionaire venture capitalist. When Rauner was found not to have standing, Janus was allowed to pursue the suit.

Janus is a child-support worker employed by the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. “The union voice is not my voice,” Janus wrote in a Chicago Tribune op-ed. “The union’s fight is not my fight. But a piece of my paycheck every week still goes to the union.” His lawyers will argue before the Court that if “money is speech” in a post-Citizens United world, then fair share fees are unconstitutional “forced” or “coerced” speech.

The Court decided 40 years ago in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education that fair share fees are constitutional. The decision tried to balance the right of a union to exist against the rights of any workers who don’t want to be members. Since unions must represent all employees in contract negotiations, the Court held that nonmembers could be assessed a fee to cover the costs associated with this representation. But, the Court said, nonmembers could not be charged for costs associated with political activities. Today, fair share fees and political fees are separated. The Abood decision is not a good enough compromise for the Janus lawyers, who argue everything a public-sector union does is political.

Overturning Abood would be “a right to a free ride, nothing more, nothing less,” says Joel Rogers, a University of Wisconsin law professor. “There’s no question that it’ll have a devastating financial effect on public-sector unions, at least in the short tem.”

THE TROIKA

Media coverage has focused almost uniformly on the personal stories of Mark Janus and Rebecca Friedrichs, and the complex legalities of their cases. That coverage obscures the bigger picture.

“It’s a mistake to focus on the individual plaintiffs,” says Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, an assistant professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University. “Instead, the focus should be on the conservative advocacy groups. … ALEC, SPN and the Kochs’ Americans for Prosperity have all worked hand in glove over the past several years to cut back the strength of public-sector unions. The effects of this case will be felt far beyond the plaintiffs.”

Infographic design: Rachel Dooley

ALEC was founded in 1973 as a venue for politicians and corporate lobbyists to meet behind closed doors and draft cookie-cutter legislation, known as “model bills,” that promote corporate interests. The Center for Media and Democracy published ALEC’s library of secret bills in 2011. One stack of model bills aims to privatize public services and public schools; another stack aims to break unions.

Americans for Prosperity (AFP) is a right-wing political advocacy group founded by billionaire brothers David and Charles Koch, owners of Koch Industries. AFP, fueled by a large network of millionaire and billionaire funders, spends millions on TV ads in election cycles and serves as the Kochs’ “grassroots” lobbying arm. AFP representatives participate in both ALEC and SPN.

SPN is the least well-known of the three groups, in part because it is made up of dozens of innocuous-sounding “institutes” and “centers” like the Illinois Policy Institute and the Mackinac Center. Yet SPN’s 66 think tanks and 87 associated groups take in more than $80 million annually, eight times the budget of ALEC.

SPN’s predecessor, the Madison Group, was launched by ALEC in the 1980s to be a Heritage Foundation in each of the states, at the suggestion of President Ronald Reagan to millionaire Thomas Roe. Today, SPN members provide the local presence needed to make ALEC proposals appear homegrown.

The Koch brothers: Charles G. Koch and David H. Koch

In red states, SPN groups provide the cookie-cutter studies, the “expert” legislative testimony and the media commentary to back ALEC’s union-busting bills, school voucher programs and other Koch political priorities. In blue states, these think tanks use door-knocking campaigns to solicit workers to quit their unions, “recertification” efforts to force unions to vote annually on whether to exist, and lawsuits aimed at demobilizing organized labor.

“This form of ultra-conservatism is geared toward making sure that there is no organized power outside of big business and wealthy, organized donors,” says Theda Skocpol, a Harvard professor of government and sociology. For that reason, pulling back the curtain on how this machine operates and is funded is vital to workers’ interests.

The work of this “troika,” as Skocpol and Hertel-Fernandez call it, is underwritten by corporations, right-wing foundations and a handful of billionaires. Most corporate donors have managed to keep their identities secret, but ALEC’s industry advisory board, which helps fund the organization, has included representatives of Koch Industries, Exxon Mobil, Pfizer, State Farm and other giant firms. Known past funders of AFP include the American Petroleum Institute and Reynolds American. SPN’s past donors include Altria/Phillip Morris, AT&T and Time Warner.

Another big chunk of the funding for the troika—tens of millions over the past decade—flows from Donors Trust and Donors Capital, two donor-advised funds connected to the Koch brothers’ network. These funds help donors cloak their identities.

The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation in Milwaukee, with more than $900 million in assets, is another major operational funder. Harry Bradley started the foundation in 1942, shortly after the death of his brother, Lynde, with profits from their electronics parts manufacturing company. Like the Koch brothers’ father, Fred Koch, Harry was a big supporter of the far-right, anti-civil rights John Birch Society. He frequently hosted its founder, Robert Welch, for public presentations at the company’s Milwaukee headquarters. Today, Bradley is one of the SPN network’s biggest benefactors, funneling $133 million to network groups since the 1980s. Bradley has also funded ALEC and AFP.

Across the country, in statehouses and in court, the troika has transmuted this flood of money into a two-pronged attack on unions. But, Skocpol says, “This is not what the public wants. It is entirely a political effort to destroy the most significant, organized political counterweight to the extreme Right.” In fact, the popularity of unions is on the rise. A 2017 Gallup poll found that the percentage of Americans who approve of unions had risen 5 points in a single year, to 61 percent, the highest since 2003.

IN THE STATEHOUSE

A trove of Bradley Foundation documents were leaked in 2016 by a sophisticated group of international hackers. The documents reveal the inner workings of a 15-year effort to build infrastructure in battleground states to support the Republican Party and tear down unions.

In 2003, Bradley launched its disingenuously named Working Group on Employee Rights at a private meeting in Washington, D.C. The group included Grover Norquist of Americans for Tax Reform (an SPN member) and Paul Kersey, who has worked for the National Right to Work Committee, the Illinois Policy Institute and the Mackinac Center, three of the nation’s premier union-busting operations. A later meeting would bring in ALEC, SPN and the anti-union front group Center for Union Facts. What emerged is a stream of underwriting for think tanks, anti-union litigation efforts, anti-union media groups, opposition research shops and even an anti-union alternative to teachers unions (the Association of American Educators).

Bradley Foundation board chair and multimillionare James Arthur “Art” Pope (L) and Bradley board member and billionaire Diane M. Hendricks

In 2009, Bradley CEO Michael Grebe, once an attorney for the Republican National Committee, backed a little-known county executive, Scott Walker. Grebe took a highly unusual step for a “philanthropist,” becoming the chair of the Walker campaign for governor.

As a result of the financial crisis, Democrats were swept out of office in 2010 and a wave of Republicans took control of 26 state legislatures (up from 14) and six new governors’ mansions. This was the opportunity the groups had been waiting for.

Bradley suddenly ramped up its annual giving to AFP from $20,000 to $520,000. The head of AFP, Tim Phillips, visited Walker before he was sworn in, urging him to provoke a showdown with public-employee unions. The group was working on a similar strategy in Indiana, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

Weeks after taking office, Walker declared that Wisconsin was facing a dire financial crisis and introduced his Act 10 “budget repair bill,” which would slash $900 million in school spending and gut the state’s collective bargaining law. Walker justified the bill by declaring repeatedly that the state was “broke.” But in a Congressional grilling a month later, when pressed by Ohio Rep. Dennis Kucinich on how much money the measure would save, Walker admitted, “It doesn’t save any.” (Similarly, when Rauner issued his executive order to block fair share fees, he claimed budget deficits forced his hand, but in front of a friendly audience at the Hoover Institute in California, he admitted that the executive order had “nothing to do with any of the budget.”)

The Wisconsin gambit has been repeated in red state after red state. All told, 15 states have passed bills restricting collective bargaining by public workers, and six states—Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Missouri, Kentucky and West Virginia—passed ALEC union-busting right-to-work bills despite mass protests. In some states, the public has taken to the ballot to turn back the attack: Voters in Ohio reversed the measure with a veto referendum in 2011; Missouri has a referendum on the ballot for 2018.

IN THE COURTS

States under Democratic control required different strategies. A blitzkrieg of lawsuits against unions were unleashed, including the 2012 Knox v. SEIU in California, the 2014 Parrish v. Dayton in Minnesota, the 2014 Harris v. Quinn in Illinois, the 2015 D’Agostino v. Patrick in Massachusetts, the 2015 Bain v. California Teachers Association and the 2016 Friedrichs. These cases did not originate with public workers, critics claim, but were instead initiated by right-wing lawyers who sought out clients to advance a union-busting agenda.

The National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation (NRTWLDF) supplied attorneys for most of these cases and is the lead attorney in Janus. Founded in 1968 with a mission to “eliminate coercive union power,” the foundation (along with its advocacy arm) is an SPN member with $14 million in annual revenue. NRTWLDF is funded by the usual suspects: Donors Trust and Donors Capital, the Bradley Foundation, and the anti-public-school Walton Foundation, run by Walmart’s founding family.

A long list of amicus curiae briefs from a variety of think tanks may make it seem as if the Janus side has broad national support. In fact, 13 of 19 briefs filed by organizations (rather than governments or individuals) for the plaintiff come from current or former members of SPN. Seventeen were filed by groups that have received funding from Bradley, Donors Capital and Donors Trust.

Infographic design: Rachel Dooley

Another funder of this work is the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), a trade association affiliated with ALEC and SPN that filed anti-union briefs in Friedrichs and Janus. Why should private-sector NFIB care about public-sector unions at all? In his book The One Percent Solution: How Corporations Are Remaking America, One State at a Time, political economist Gordon Lafer quotes a 2015 NFIB blog post: “Because ... if unions are dealt a blow in the public sector, private sector businesses might see decreased pressure from pro-labor forces on issues ranging from the minimum wage to paid sick leave and other employee benefits.”

Lafer, a professor at the University of Oregon’s Labor Education and Research Center, insists the corporate money behind these institutions should not be overlooked. “Who are the most serious opponents to the corporate agenda on the minimum wage, paid sick leave, health insurance and NAFTA free trade?” Lafer asks. “[Corporations] think they will get rid of their best-funded opponents on a whole range of issues.”

DEFUNDING THE DEMOCRATS

Grover Norquist is excited about a potential Janus victory for another reason. “Seven million public-sector employees who pay between $4 billion and $8 billion a year in dues—a third of them will quit [paying],” he told The Atlantic. “Now try funding the modern Democratic Party without union dues—good luck.”

While fair share fees do not directly fund union political activity, any loss of funding could weaken a union’s organizational capacity, ultimately undercutting electoral clout. According to FollowTheMoney.org, unions contributed an estimated $602 million to state and federal races and ballot initiatives in 2016. Slightly more than half of that ($319 million) came from public-sector unions. In 2016, labor was the largest contributor to state-level Democratic candidates, accounting for at least 18 percent ($128.7 million) of their total fundraising. Unions also mobilize their workers as persuasive door knockers at election time who can explain who they are and what they fight for.

Research by academics like Columbia’s Hertel-Fernandez suggests that the erosion of public-sector union membership by ALEC bills has also dampened political participation. His most recent study, based on data from 1980 to 2016, shows that right-to-work laws decrease Democratic presidential vote share by 3.5 percent and depress overall turnout.

behind closed doors

It would be imprudent for Bradley or SPN to be as blunt as Norquist in public (given their tax-exempt status as charitable organizations), but internal Bradley and SPN documents are clear about their goal of bleeding the Democratic Party of funding.

Norquist has long described unions, public-sector workers and trial lawyers as the funding “pillars” of the Democratic Party. In internal documents prepared for its board of directors, Bradley staff channels Norquist and recommends continued funding for the NRTDLF because “big Labor and trial attorneys … are the two principal funding pillars of the Left.” Bradley has gifted the anti-affirmative action Center for Individual Rights, which represented the Friedrichs plaintiffs, with more than $1.5 million.

Materials prepared for the Bradley board track Friedrichs and the cases leading up to it. A map from the pro-worker Economic Policy Institute is included to show states that allow fair share fees, annotated to show the potential monetary losses for unions at $500 million to $1 billion per year. Bradley staff quote “the leftist In These Times,” which characterized Friedrichs as a case “that could decimate public-sector unions.”

Another case leading up to Janus was Bain v. California Teachers Association, which attacked the way the union processed political fees. Bradley staff called Bain and Friedrichs combined a “powerful ‘one-two’ punch” against unions, predicting that “all that would remain to fund the unions’ political apparatus would be the hardcore teacher members.”

For Bradley, the anti-union work was a twofer. Bradley has long been a proponent of the privatization of America’s schools; America’s public school teachers and powerful teachers unions stand in the way. Internal documents show Bradley staff bluntly advocating projects to “defund teachers unions and achieve real education reform” at the same time.

“Teachers unions are at the heart of all this,” says Harvard’s Theda Skocpol. “Teachers exist in every community across the country. They are educated, they speak up, and they care about public schools. Break the teachers unions and you break the organizational power that exists in and around the Democratic Party at the state and local level.”

In an April 2016 fundraising letter obtained by the Center for Media and Democracy and published in the Guardian, SPN CEO Tracie Sharpe asks her readers to help strike “a major blow to the Left’s ability to control government.”

I am writing you today to share with you our bold plans to permanently break the power of unions this year. ... I am talking about the kind of dramatic reforms we’ve seen in recent years in Indiana, Wisconsin, Michigan and now West Virginia—freeing teachers and other government workers from coercive unionism—and spreading them across the nation. … I’m talking about permanently depriving the Left from access to millions of dollars in dues extracted from unwilling union members every election cycle.

SPN’s secret union-busting toolkit even celebrates this February 2016 quote from a Wisconsin AFSCME leader talking about the devastating impact of Walker’s Act 10 bill: “Do we have less boots on the ground? Yeah. Do we give the same amount of money to candidates? No.”

The Freedom Foundation in Olympia, Wash.—a featured and feted SPN member—has been equally explicit in its fundraising letters. One 2014 letter obtained by the Guardian reads, “The Freedom Foundation has a proven plan for bankrupting and defeating government unions through education, litigation, legislation and community activation.”

A Freedom Foundation-produced brochure, titled “Undue Influence: Public Unions’ Cycle of Power, Electioneering,” shows multiple charts and graphs on union spending in campaigns and elections. The graph “Democrats’ Dependence on Union Funds” lists 31 Washington state Democratic legislators and their union campaign contributions. The accompanying text argues that “the problem associated with union electioneering” could be solved by weakening unions and eliminating fair share fees.

SPN member groups have also cited their union-busting efforts as key to electing Trump. The Wall Street Journal profiled Tracie Sharpe in a post-election puff piece on its editorial page, titled “The Spoils of the Republican State Conquest.” She tells the paper that Wisconsin and Michigan were only “thinly blue” and that the destruction of the states’ unions has put the GOP on better footing. “When you chip away at one of the power sources, that also does a lot of get-out-the-vote,” Sharpe chirped. “I think that helps—for sure.”

Unions lost 136,000 members in Wisconsin; Trump won by 23,000 votes. “Did the labor reforms enacted in Wisconsin and neighboring Michigan help Donald Trump win those states?” asks Norquist associate Matt Patterson in the Daily Signal. “No question in my mind. Hard to fight when your bazooka’s been replaced by a squirt gun.”

Most of the groups pursuing this agenda, including Bradley and SPN, are tax-exempt charitable groups. After Citizens United ushered in a surge of dark money groups, the Obama administration’s IRS attempted to distinguish real charitable organizations from false ones, only to have the effort shut down by tremendous blowback from the Right. Ever since, the IRS has been reluctant to take action on these kinds of issues.

“There is simply no basis in law to find that defunding or attacking unions is a tax-exempt charitable activity,” says attorney Marcus Owen, former director of the IRS’s exempt organizations division. “On the contrary, such actions are deeply infused with private benefit to employer interests and political party interests—but not with community or public benefit, which is required under the law.”

DEGRADATION OF CRITICAL SERVICES

The Democratic Party is not the only loser in this scenario; real harm will be done to U.S. workers and their families. Following World War II, unions expanded dramatically, representing 35 percent of the workforce at their peak in the mid-1950s and helping to usher in an era of shared prosperity. According to the Economic Policy Institute, unionized workers make 20 percent more, on average, than other workers, but their ranks have shrunk to 6.5 percent of private-sector workers and 34.4 percent of public-sector workers in 2017. This decline has exactly tracked the decline of the American middle class.

The attack on public-sector workers is also an attack on women and African Americans, groups disproportionally represented in public-sector unions. According to a National Women’s Law Center analysis, women make up 55 percent of union-represented public-sector workers, and a 2010 analysis from the Center for Economic and Policy Research shows that African Americans are 30 percent more likely than the overall workforce to hold public-sector jobs.

One silver-lining argument contends that an adverse Janus ruling presents an opportunity for unions to simply do their job better: Talk to every member, innovate on services and benefits, and do the kind of “deep organizing” needed to outmaneuver wealthier opponents. The data from Wisconsin, however, is not encouraging. Five years after Walker’s draconian Act 10 bill, Wisconsin’s union membership rate had dropped from 14.2 percent to 8.3 percent of the workforce. The impact of Janus would be less immediate but would snowball over time: Weaker, less effective unions have a harder time attracting members.

“If fair share fees are struck down, it simply won’t be possible to provide the expertise to bargain with employers to increase wages and benefits,” says John Matthews, the retired executive director of Madison Teachers Inc., a National Education Association affiliate in Wisconsin.

The erosion of public-sector unions means that public-sector jobs will pay less and become less attractive, degrading not just a source of good jobs but the critical public functions these workers serve. The average annual salary and benefits for teachers in Wisconsin dropped by $10,843 after Act 10 was passed, a 12.6 percent reduction. The result has been a staggering shortage of teachers, including an “extreme” shortage in math and science, forcing the state’s independent Department of Education to reluctantly issue “emergency” teacher’s licenses.

For the most part, the right-wing machine’s deeply financed, organized and focused attack on workers has rolled its agenda through without meaningful resistance from Democrats. To be sure, in Wisconsin, the union-busting plan was met with one of the largest sustained mass protests in labor history and a 16-day occupation of the Capitol. Fourteen Democratic state senators even fled to Illinois to block a vote on Act 10. But too often, the Democratic Party has been asleep at the switch. First Jimmy Carter, then Bill Clinton, then Barack Obama failed to pass a national “card check” program—a measure that would have made forming a union as easy as signing a postcard—while their party controlled both houses of Congress.

If the Janus verdict goes against public-sector unions, the great challenge for Democrats will not merely be one of funding, but one of leadership. Who will step up to push for the renewal of trade unions, not just for the party’s political future, but for a country that cannot progress toward economic and social justice without a prosperous and muscular labor movement?

is the deputy director of the Center for Media and Democracy (CMD). She helped launch CMD’s award-winning ALEC Exposed investigation in 2011 and is a recipient of the Hillman Prize for investigative journalism.

This story was supported by the Leonard C. Goodman Institute for Investigative Reporting. David Armiak and Elena Sucharetza provided research assistance.

Want to stay up to date with the latest labor news? Subscribe to the free In These Times weekly newsletter: